How Can AI Prosumers Build AI Tools At Work?

Explore the shift from engineers building each AI tool for employees to creating a platform that empower every employee to become an AI assistant builder.

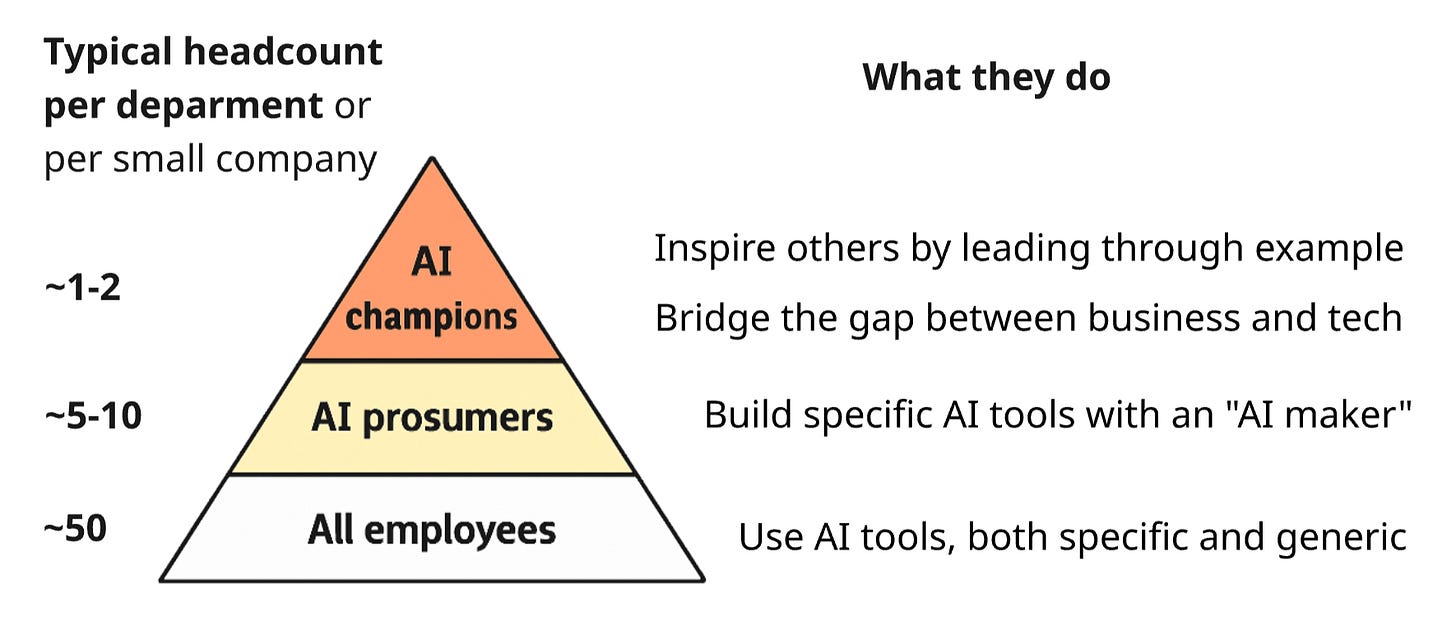

You may have heard of AI champions—AI enthusiasts who understand both business objectives and GenAI's capabilities deep enough to lead the AI adoption in the workplace.

Recent MIT NANDA report goes further. It claims that AI adoption and ROI are higher when deployment starts with initiatives from employees and line managers, which they call "prosumers"—producers who are also consumers.

These employees produce small AI tools for their own use, and if a company encourages their initiatives, such tools can become a basis for valuable and efficient "bottom-up" AI deployment. The number of AI prosumers in a company can be much larger than that of AI champions, as the former are not required to understand the business or possess leadership skills. Prosumers bridge the gap between unapproved ChatGPT use at work (referred to as "Shadow AI" in the MIT research) and company-wide AI initiatives.

Thus, in the context of this post, prosumers are non-technical builders of AI tools. In my view, there is a good reason for their positive impact on AI adoption metrics and even ROI. As prosumers build AI tools themselves, they gain a sense of ownership and become motivated to use the tools and recommend them to their colleagues. This is similar to properly implemented Scrum, where teams make their own decisions about what and how to build, fostering a sense of ownership and increasing business value.

Let's consider the practical steps required to implement this bottom-up approach in an SMB.

1. The Missing Type of AI Tool

According to the same report, to solve a noticeable percentage of workplace tasks, not only universal but also specialized AI tools are needed. There should be many of them, and each should contain instructions and other context from an employee with experience solving such tasks.

Below, I will refer to such specialized AI tools more specifically as "AI assistants". This is to avoid ambiguity, as "tools" in the context of AI also refers to API functions used by AI agents, not people. The term "AI copilots" can also be used, although this term, thanks to Microsoft, often creates incorrect associations.

To summarize the main benefits of the mass creation of AI assistants, which I described in my previous post:

Employees save time, as the main prompt and context are already set inside the assistant.

Since such AI not only helps but also guides, beginners learn better and get good results from AI much more often.

As a result, multiple assistants can serve as a practical skills base—partially replacing a knowledge base. These are not just passive instructions but guides with which even an inexperienced employee can solve the necessary task in minutes.

2. Employees As Assistant Builders

Currently, companies involve technical specialists in creating AI assistants. But there should be many specialized assistants, so it's too expensive to involve an engineer for each.

Unlike AI engineers and software developers, the prosumers described above have domain expertise, making their AI micro-products well-adapted for their domains. However, they can't code or even no-code, and their prompting skills are usually worse than those of software engineers.

How can we help such employees build the assistants described above?

In my previous post, I considered basic ways of providing such help. These are not so much technical solutions as organizational ones:

Employee access to an AI platform with the function of creating GPTs-like assistants.

A catalog of system prompts or even a meta-assistant for creating such prompts.

Training employees in AI basics and prompting.

Training and motivation for AI champions who spread the best AI practices in the company.

Motivation for AI assistant authors—including social motivation—for example, hackathons.

In this post, I will consider the first technical solution to help prosumers.

3. New Solution: AI Assistant Maker

The goal of "Giving all employees the ability to build their own AI assistants" can only be achieved through what all employees can do—communicate in natural language.

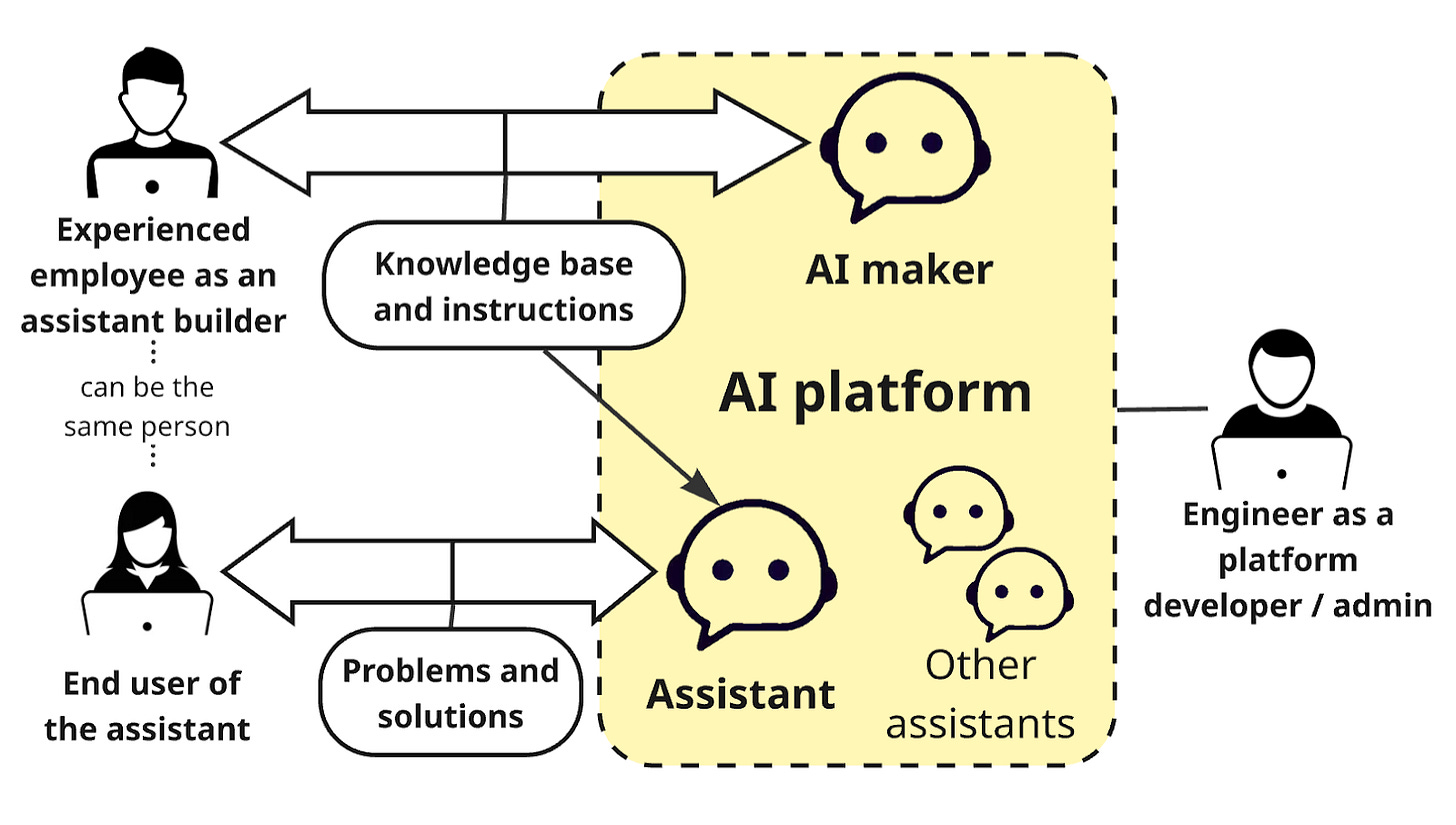

Therefore, a "homemade" AI assistant adapted to specific tasks should be built by communicating with another AI assistant, which I will further call an AI maker.

Any assistant built with AI maker should include a quality system prompt and, possibly, a knowledge base related to such tasks to add to the LLM context through RAG (RAG is a standard feature of corporate AI platforms). Accordingly, the AI maker should be able to:

create and edit assistants with system prompts in the AI platform,

link knowledge files from the user (whom we will call an "assistant builder") to the assistant,

and most importantly—convert the user's words into a quality system prompt.

Additionally, to ensure that the assistant builder doesn't need AI qualifications, the AI maker should guide them in the right direction by asking questions.

In a small company where I work as an AI architect, I am currently developing such an AI maker.

4. Building Process From a Prosumer's Perspective

For example, consider creating a commercial proposal for a B2B customer. Let's assume that the input is a presale meeting transcript, so theoretically, it could be processed by an automatic AI workflow triggered by a "new transcript appeared" event. However, in reality, this cannot be done without a responsible salesperson who will check, correct, and supplement the result using an AI assistant.

When communicating with an assistant builder, the AI maker must first understand exactly how tasks of this type are solved (without AI). At this stage, it may turn out that such an assistant cannot be built with the available technical means (the maker should have a checklist on this topic). And this is also a good result: the employee will not waste time on an unsolvable task. For example, a salesperson might want the commercial proposal to be automatically uploaded to the CRM as a PDF, but the AI platform doesn't have such tools yet.

Next, the maker requests missing details from the builder and ultimately forms the system prompt for the assistant. In my experience, it's very useful to give the builder the system prompt for direct editing. Even if the person doesn't have a technical background, when reading such prompts, valuable improvements occur to them, and they are quite capable of making them directly in the prompt. For example, a salesperson can add keywords that may select one of the company's accepted contract types. And then the AI will correctly select the commercial proposal template.

The next step is testing the assistant by the builder. Until this point, my maker doesn't request "context" from the builder (the content of the assistant's knowledge base), as it's difficult to understand in advance what context is missing. Only at the stage of collecting feedback on the assistant's work does the maker suggest that the builder copy examples or upload files that will improve the quality of results. For example, these could be sample commercial proposal files that should be used as a basis when generating new proposals by the assistant.

5. AI Platform Implementation Options

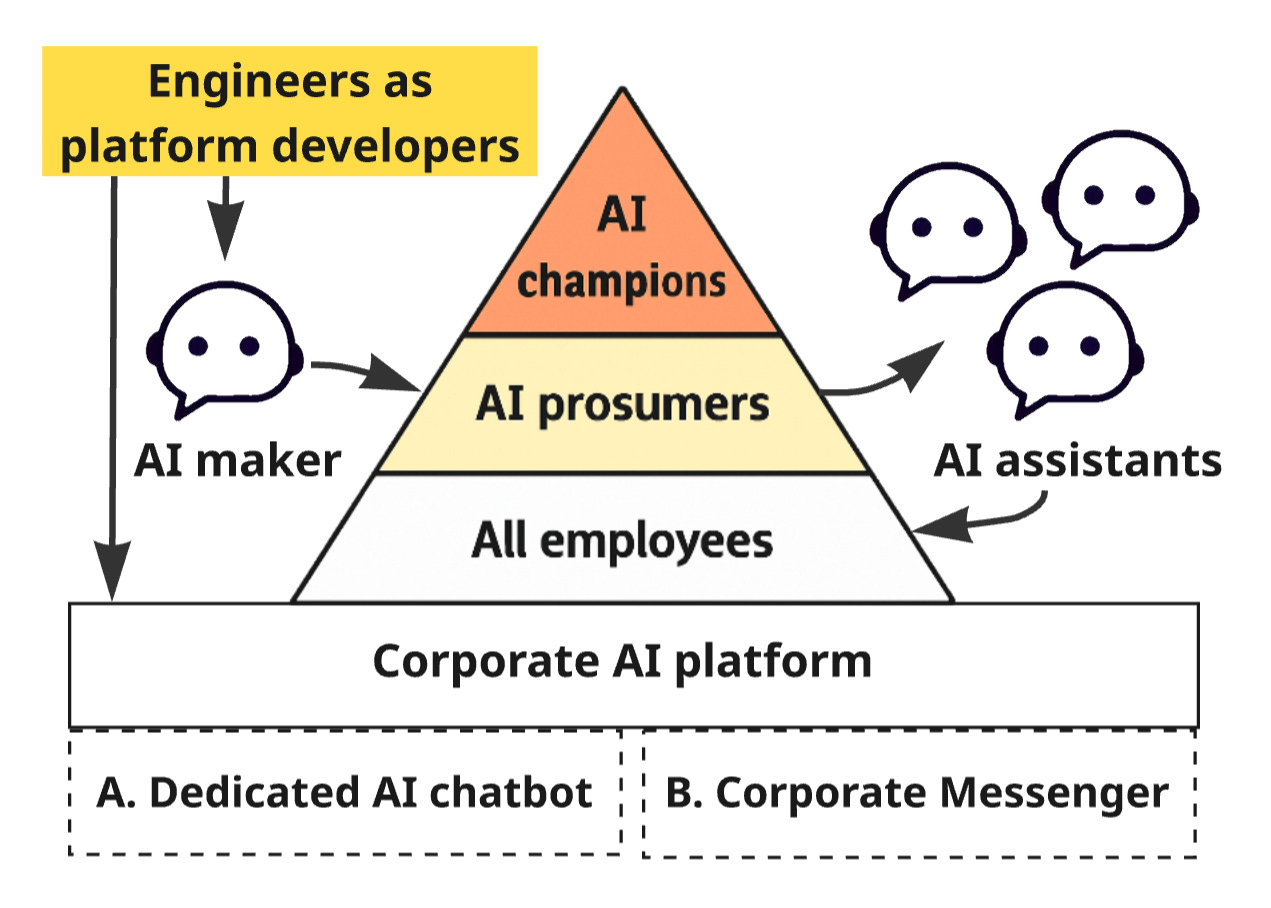

To make this possible, an AI platform designed for end users should also be configured for building assistants. Such a platform contains a lot of organization-specific information on the backend—for example, information about specific data storages and SaaS that the user and AI can interact with.

Of course, such a platform is not developed from scratch for each company, especially if it's an SMB. There are several options to save the engineering effort required for the platform; here are two of them.

Option 1: Dedicated AI Chatbots

The platform can be based on ready-made open-source products in the "AI chatbot" category. They save you from the labor-intensive work of developing a ChatGPT-like UI. Ideally, such a product should already support the concept of AI assistants analogous to GPTs. For example, this concept is supported by Dify.ai, which is complex to deploy and configure but allows for deep customization using plugins.

Alternatively, Open WebUI is one of the most popular products of this kind—due to its relative ease of deployment and configuration. In Open WebUI, assistants are called "models," and these models can be created by end users, not just admins. Despite the low customizability of Open WebUI compared to Dify, such assistants can be created programmatically: see Functions/Pipe.

To save effort on the programmatic implementation of assistants in OpenWeb UI, you can use external APIs instead. This isn't a big deal, because it's still necessary to connect an external API for RAG, as this gives better speed and quality compared to the RAG mechanism built into Open WebUI.

Specifically, R2R API has not only RAG, hybrid search, and web search tools but is also a stateful backend for assistants—thanks to Conversations. These conversations preserve chat context, enabling coherent multi-turn interactions with the assistant. When using R2R, Open WebUI only performs the role of UI, and the custom code of the AI platform is just a small control layer between the UI and the R2R backend.

Option 2: Messenger Extensions

The platform can work as an extension to a corporate messenger (for example, Slack), which is much easier to develop than a full-fledged platform with its own UI. In Slack, AI assistants and an AI maker can be built as apps, and auxiliary services for them can be implemented as workflow automations. Open-source messengers like Mattermost are even more customizable to host a "corporate AI platform."

Option 2 is worth considering, as it's difficult to make people use a separate AI platform (Option 1):

The aforementioned MIT study shows the "Shadow AI Economy": most employees use ChatGPT and ignore the corporate platform, which is inferior to ChatGPT in quality and usability. In contrast, employees use a corporate messenger on a daily basis (except for those companies that conduct all communications via email). So, AI in the messenger can't be ignored.

Moreover, AI becomes more comprehensible to people if they address it in the same way as they would a subordinate or other colleague. For example, if a colleague didn't help with a question, you can mention an AI assistant/agent in the same chat. Or vice versa.

6. The Role of Engineers

So, engineers should develop the "corporate AI platform" that supports the creation of full-fledged AI assistants by non-engineers. But why not involve developers in building the assistants themselves? Given their higher qualifications in AI, wouldn't the quality be better? Probably not.

It makes more sense to assign engineers to create only common AI assistants—for example, a "Helpdesk for IT & HR-related FAQs" or a "Q&A assistant for the corporate project documentation database." Companies usually start implementing AI with assistants of this type, but only few of them are truly useful.

In the second phase of AI deployment, it's better to create specialized, "homemade" assistants by non-engineers' hands.

Why should we focus developers on the platform rather than on specific AI tools for employees?

First, motivation. The platform is exactly what developers are used to doing: a large, technically complex product that is easily expandable and flexibly adapts to the needs of different users. They are typically more motivated and efficient when working on such a product than when configuring a series of small applications—in this case, specialized AI assistants. For them, creating AI assistants feels like "technical support" rather than building something new, which the "platform" represents.

Second, cost, and not just the cost of the developers' time. Communication between a domain expert and an engineer usually takes a lot of time. For them to understand each other, a specially trained person, such as a product manager or an analyst, is often required. However, engaging in such complex communication is not feasible for a single assistant that only simplifies onboarding and improves the efficiency of a few employees.

Conclusion

A significant proportion of companies are already solving problems that hinder AI adoption in the following ways:

They give people access to an AI platform with support for custom assistants and even "agents."

[less often] They introduce the role of AI champions and conduct training for them and other employees.

[sometimes] They encourage regular team and cross-team meetings to exchange experience, although such initiatives only work for the first few months as people run out of things to talk about.

[very rarely] Companies hold hackathons for non-technical employees and give them basic tools for building assistants, such as examples and templates of system prompts.

The AI maker-based approach described in this post is the next step toward real AI adoption and ROI.

However, this is far from being the last step.

I see further development in specialized assistants built by non-technical employees becoming more and more powerful. For example, they should be able to adapt to changing needs ("self-learn"), solve multi-step tasks with logical branches, and use agentic tools. In specialized assistants, these powerful features should appear almost simultaneously with their release inside "universal" AI assistants like "Helpdesk," which are initially developed by engineers.